Eruvin Daf Ten

ūÉųĖū×ųĘū© ū©ųĘūæ ūÖūĢų╣ūĪųĄūŻ: ū£ųĖūÉ ū®ūüų░ū×ų┤ūÖūóųĘ ū£ų┤ūÖ ūöųĖūÉ ū®ūüų░ū×ųĘūóų░ū¬ų╝ų░ū¬ųĖūÉ.

Rav Yosef said: I did not hear this halakha of Rabba bar Rav Huna from my teachers. Rav Yosef had become ill and forgotten his learning, which is why he could not recall the halakha that a side post that is visible from the outside is considered to have the legal status of a side post.

for Video Shiur click here to listen: Psychology of the DAF Eruvin 10

Nedarim 41a

ū©ūæ ūÖūĢūĪūŻ ūŚū£ū® ūÉūÖūóū¦ū© ū£ūÖūö ū¬ū£ū×ūĢūōūÖūö ūÉūöūōū©ūÖūö ūÉūæūÖūÖ ū¦ū×ūÖūö ūöūÖūÖūĀūĢ ūōūæūøū£ ūōūĢūøū¬ūÉ ūÉū×ū©ūÖūĀū¤ ūÉū×ū© ū©ūæ ūÖūĢūĪūŻ ū£ūÉ ū®ū×ūÖūó ū£ūÖ ūöūōūÉ ū®ū×ūóū¬ūÉ ūÉū×ū© ū£ūÖūö ūÉūæūÖūÖ ūÉū¬ ūÉū×ū©ūÖū¬ūö ūĀūÖūöū£ū¤ ūĢū×ūöūÉ ū×ū¬ūĀūÖū¬ūÉ ūÉū×ū©ūÖū¬ūö ūĀūÖūöū£ū¤

The Gemara relates: Rav Yosef himself fell ill and his studies were forgotten. Abaye restored his studies by reviewing what he had learned from Rav Yosef before him. This is the background for that which we say everywhere throughout the Talmud, that Rav Yosef said: I did not learn this halakha, and Abaye said to him in response: You said this to us and it was from this baraita that you said it to us.

Rabbenu Chananel Eruvin

ūøūō ūŚū£ū® ū©ūæ ūÖūĢūĪūŻ ūÉūÖūóū¦ū© ū¬ū£ū×ūĢūōūÖūö ūĢūÉūĀū®ūÖūÖūö ū×ū”ūóū©ūÖūö ūĢūóūō ūÉūÖū¬ūżūŚ ūÉūöūōū©ūÖ ū£ūÖūö ūÉūæūÖūÖ.

He seems to explain her forgot his learning from the distress of the illness

Ran Nedarim

ūÉūÖūÖū¦ū© ū£ūÖūö ū£ūÖū×ūĢūōūÖūö - ūöūøūæūÖūō ūóū£ūÖūĢ ū£ū×ūĢūōūĢ ū®ū®ūøūŚūĢ:

He seems to have a different text, and that his learning was “too heavy”, and he forgot it. This sounds more like burnout.

The following is excerpted and summarized from a study, conducted by Daphne Norez, Fort Hays State University. (Norez, Daphne, "Academic Burnout In College Students: The Impact of Personality Characteristics and Academic Term on Burnout" (2017). Master's Theses. 502. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/502):

Burnout is a condition which can affect people in a variety of settings. It is associated with reduced productivity and satisfaction; increased rates of mood disorders such as depression and anxiety and a plethora of physical problems including increased inflammation biomarkers and cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, sleep disturbances, changes in appetite, fatigue, lowered immunity, headaches, and gastrointestinal distress. Burnout has primarily been studied as an occupational hazard, but there is increasing evidence that it is a condition that can be experienced in other settings, such as school.

Originally, the condition of burnout was noted particularly in service occupations, such as health care, teaching, social work, counseling, and law enforcement (Maslach & Schaufeli, 1996). These are intense and demanding fields, requiring close interaction with others and high degrees of empathy and competency. Those who choose to enter service occupations tend to be idealistic, with “lofty goals to help and serve others” (Schaufeli, Leiter, & Maslach, 2009, p. 206). When faced with the limitations imposed by reality, some people can begin to feel discouraged and cynical. The expectations of those being served, and of society in general, have intensified over time, even while financial and societal support, have decreased (Schaufeli et al., 2009). This has led to a discrepancy in the ratio of the effort exerted to the reward realized (Schaufeli, 2006). In addition, negative outcomes of interactions in these fields can be very damaging, even catastrophic, for those with whom providers come into contact. This knowledge places a great deal of pressure on those in service occupations. It is also possible that burnout is most recognized in these fields because people in these fields are more attuned to matters of mental health and are better able to identify the signs of impending burnout. In any case, the rapid evolution of our society from an industrial one to a service-oriented one in 3 the latter quarter of the 1900’s likely fostered and accelerated the development of the phenomenon of occupational burnout (Schaufeli et al., 2009)

Theoretical Approaches Research on the topic of burnout tends to take one of three primary approaches. Most of the literature reflects an organizational approach, focusing on job factors like workload; work-related resources; interpersonal relationships with coworkers, supervisors and clients; work environment and so on (Maslach & Schaufeli, 1996). The idea behind this approach is that organizational factors exert excessive stress on the individual (Weber & Jaekel-Reinhard, 2000). The demands-control model is based on this basic perspective. It proposes the most stressful situations are ones where the individual has high demands placed on him/her, but has little control over how the work is done or how the organization functions. Other models which fall into this category are the job demands-resource model and the effort-reward-imbalance models of burnout. While each has its own point to make, they are all similar in that they suggest job strain, and ultimately burnout, is caused by an imbalance in the performance demanded of the individual versus the ability of the individual to meet the demands. A second approach to the study of burnout looks at the interaction between the individual and his/her work environment/occupation to determine the degree of fit or misfit in that dynamic. In this model, the chronic strain which leads to burnout is caused by the accumulation of psycho-mental/psycho-social stress paired with lower levels of stress tolerance (Weber & Jaekel-Reinhard, 2000). Research which investigates the 7 conflict between personal values and the aims of the organization is an example of this sort of model. The third major approach taken by researchers studying burnout is to look at it from an individual perspective. Of the three approaches, this is the least explored by research. Most of the studies which have focused on personal factors have looked at demographic variables, such as age, gender, etc. (Maslach & Schaufeli, 1996). Other personal factors which have gained some attention are personality, social support, and personal values (Maslach & Schaufeli, 1996). These sorts of factors are becoming more popular among researchers seeking to establish a knowledge base about the personal contributors to burnout. Personality is perhaps one of the easiest of these characteristics to measure, due to the widespread availability of valid and easy to administer measurements of personality.

Burnout is influenced by many factors; some of which are within the individual’s power to change, and some of which are not. Personality factors are relatively stable across the lifespan. Those who report higher levels of personality traits such as introversion, lack of direction or neuroticism appear to be more susceptible to burnout and other negative emotional states. Identifying these individuals could make it possible to intervene and teach more adaptive coping skills in order to reduce the likelihood they will experience burnout in the future.

When it comes to Torah study, the aspects of academic burnout and occupational burnout merge. For many, learning is an occupation. “Torah is the bester sechoireh”. In learning, the challenge is that without defining success, there is no definition. No matter how smart you are, you come face to face with the most brilliant minds of the two millenia of lomdus. Some people, may never feel successful in learning even if they learned successfully for years. Therefore, success cannot be defined by knowledge attainment. There are different ways to look at success. Success might be defined as learning with hasmoda and keeping a seder. Success may be defined as making a siyum. Success may be defined as achieving a certain level of dvekus and yiras shamayim during the learning. Whatever the case may be, to avoid burnout, the criteria for success must be challenging enough to feel satisfaction, but realistic and not too perfectionistic to make it all but attainable.

for Video Shiur click here to listen: Psychology of the DAF Eruvin 10

Translations Courtesy of Sefaria

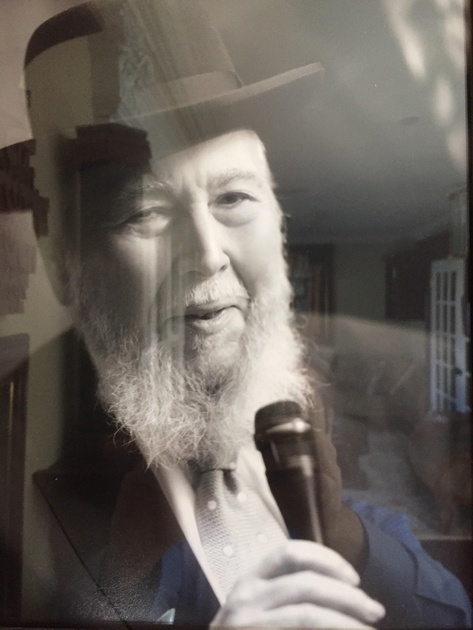

Photo Abba Mari Rav Chaim Feuerman, Ed.D. ZT"L Leiyluy Nishmaso

Previous

Previous